Who built North Carolina's state capitol? New project tells stories of enslaved workers

A new online project by state historians traces the names and stories of some of the enslaved workers who built North Carolina's historic Capitol from 1833 to 1840.

Posted — UpdatedRetracing the lives of enslaved workers is often difficult. They weren’t named in the federal census until 1850. State historians had to turn to newspapers, receipts, personal correspondence and payroll records to find the workers’ names and determine familial relationships.

Kara Deadmon is one of the three researchers who put the project together, along with Terra Schramm and Natalie Rodriguez. Deadmon told WRAL News the work started in December of 2019 when they discovered a document that was a report to state lawmakers in 1834, listing the names of all the people working on the Capitol's construction and whether they were enslaved people.

“It was the first time we saw the first and last names of some individuals,” Deadmon said. “We went from there, building an internal database of research for over 130 men and eventually using a lot of it to put together the individual stories the website features.”

The current state capitol building was built from 1833 to 1840, after the previous one burned down. It was a major project for the time, so the state needed a lot of laborers. A lot of the wealthier slave owners here in Raleigh basically rented some of their enslaved people to the state to bring in money.

Many of them were listed on payroll records as laborers, so they would have done whatever work they were needed for – like making bricks or doing carpentry. Others worked in the quarry, which was just south of downtown, cutting and hauling the stone blocks to the building site.

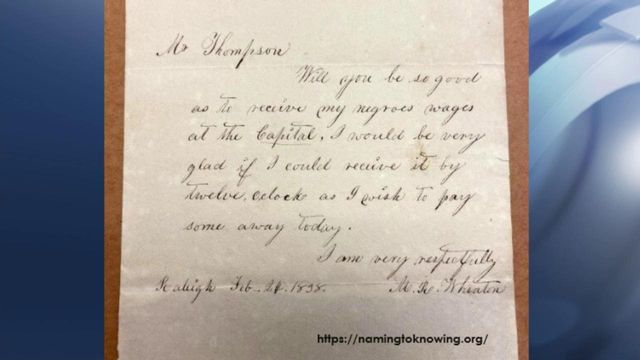

Most of them earned about 50 cents a day, and the money usually went to their owners. There’s a letter from one owner asking the supervisor to give her the pay for her enslaved person that day so she could use it to pay bills.

Others were more specialized workers, like Handy Lockhart, one of the workers profiled on the site. He was a furniture and cabinet maker who helped build the mahogany chairs and desks where state lawmakers of the day would sit during session. The desks are still in service at the Capitol to this day.

Many continued to work at the tasks they had done as enslaved people. Some were able to buy property in what became known as Cameron village, a neighborhood established by freed Black people northwest of downtown Raleigh.

Lockhart became one of the two first Black aldermen of Raleigh and a successful businessman as a furniture and coffin-maker and undertaker. He was a community and church leader for decades and worked to improve education for Black children.

“Sometimes researching the stories of enslaved people is difficult because those keeping written records during slavery were white people, often enslavers themselves,” Deadmon said. Marriages of enslaved people also weren’t officially recorded until after Emancipation Day in 1865.

The team used census data from 1850 and after, state archives, revenue and comptroller’s reports, and even genealogical websites.

“UNC Greensboro has a runaway slave ad database, and we could find some of our individuals there,” Deadmon said. “We looked at things like property deeds. Slavery was a system that considered people as property.”

“We were always kind of mentioning [to tours] that we knew enslaved people were here, but that we didn’t know specifics,” Deadmon said. ‘We realized in 2019 that we wanted to make this a priority.”

Deadmon said the pandemic, which shut down the museum for months, gave the team time for a deep dive into the research. She said it’s an opportunity to right a historical wrong.

“The names of these enslaved people existed in state documents produced at the time, but it was intentionally erased throughout the Capitol's history,’ Deadmon said. “These weren't stories that were being told in this space.”

“So we want to remedy that. We want to say the names of these individuals all the time in our building. And we want to remember that the Capitol would not exist without them,” Deadmon continued. “The Capitol is a memorial to their skill, to their talent, to their lives.”

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.