When a governor sues the state

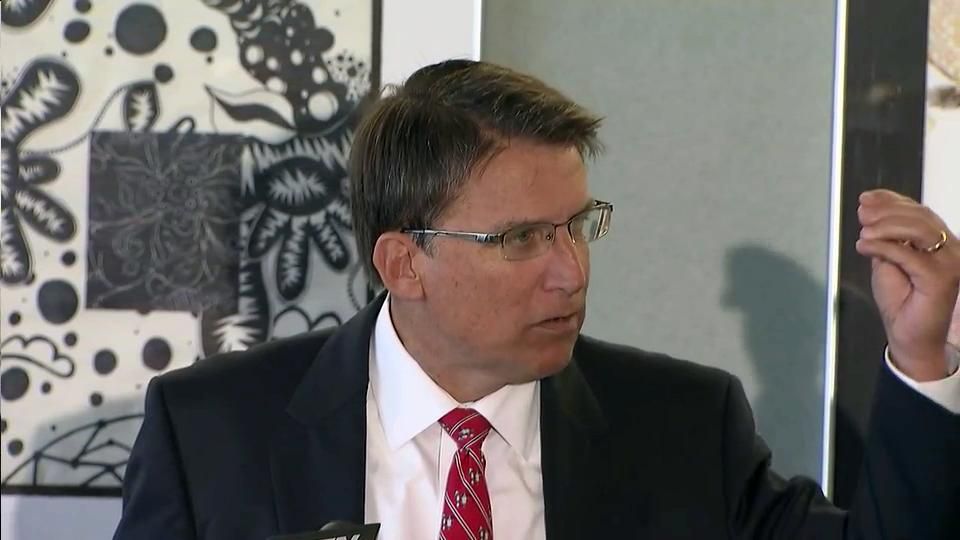

So, when you're the state's lawyer, who do you side with when Gov. Pat McCrory sues the leaders of the General Assembly?

"What we are actually doing is defending the constitutionality of the law," Chief Deputy Attorney General Grayson Kelley said this week. In effect, that means Kelley and his boss, Attorney General Roy Cooper, a Democrat, will be defending the Republican speaker of the House and president pro tem of the Senate against a lawsuit by McCrory, a Republican.

While this sounds something like a governmental snake eating its own tail, legal tussles between the governor and legislature are far from unprecedented.

"Historically, there's been this tension between the legislative and executive branch," said Bob Orr, a former state Supreme Court justice who is now in private practice.

Historically, the constitution has given the General Assembly more raw power than the Governor's Office, which means governors strenuously guard what they see as their prerogatives against legislative incursion.

Two of McCrory's predecessors, Gov. Jim Hunt, a Democrat, and Gov. Jim Martin, a Republican, joined him in bringing the suit. Both Hunt and Martin had run-ins over separation of powers during their administrations.

More than 25 years ago, Martin sued lawmakers because they granted the authority to appoint the director of the Office of Administrative Hearings, an executive branch agency, to the the chief justice of the state Supreme Court. In Martin's case, he was a Republican governor dealing with a General Assembly that, like the chief justice, was Democratic.

McCrory is also a Republican, as are the current leaders of the General Assembly, who vested the power to oversee the cleanup of coal ash ponds across the state in a newly created commission.

"The General Assembly has created an entity responsible for administering the laws that is independent of the executive branch," McCrory's recently filed lawsuit claims, pointing out that six of the nine members would be appointed by legislative leaders.

The suit also raises questions about a commission created to oversee certain environmental matters and a proposed Medicaid commission that would change how the state health insurance program for the poor and disabled is overseen. These boards constitute a "usurpation of the Governor’s constitutional authority" McCrory claims in his suit.

"We rely on the separation-of-powers provision in our state constitution in our complaint and look forward to an early resolution on behalf of our clients," said John Wester, a Charlotte-based lawyer for the trio of governors.

Wester declined to talk about specifics of the case, saying his clients first needed to make their pleadings to the court.

But chances are the governors would rather have the court look away from the Martin case and pay more attention to Wallace v. Bone, a separation-of-powers case that came up during Hunt's first two-term run. In that case, the state Supreme Court found that lawmakers had unconstitutionally appointed members of the legislature to the Environmental Management Commission.

"Suffice it to say, the people of North Carolina on at least three occasions, the last opportunity being as late as 1970, explicitly adopted the principle of separation of powers," the court wrote at the time. "It behooves each branch of our government to respect and abide by that principle."

But that case involved members of one branch of government, the legislature, appointing their own members to serve in another.

"The court never said the legislature can't appoint people. It just can't appoint its own members," said Gerry Cohen, the legislature's former head of bill drafting and former special counsel to top legislative leaders.

Before he retired this summer, Cohen authored a memo laying out the General Assembly's authority to create commissions and make appointments to them. His memo steps through 250 years of constitutional history, pointing out that, in the mid-1990s, a constitutional amendment that gave governors veto powers specifically mentioned bills through which lawmakers make appointments to various boards and commissions.

"If they couldn't make appointments to office, it would make no sense to say (the governor) couldn't veto appointments to office," Cohen said.

As a historical side note: The sponsor of the bill that put the constitutional amendment to voters was then state-Sen. Roy Cooper, the same Democrat who is now attorney general.

Lawmakers have said they are well within their rights to create such commissions. At the time the law passed, legislative leaders pointed out that McCrory's Department of Environment and Natural Resources was being investigated by a federal grand jury in connection with its oversight of coal ash lagoons, including the site that spilled tons of toxin-laced coal ash into the Dan River on Feb. 2.

"I believe the General Assembly fully has the authority to create those boards and commissions," Rep. Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, the Republican nominee for House speaker, said in a recent interview.

The costs associated with this intramural tussle are somewhat murky. Gov. Pat McCrory's spokesmen did not respond to requests to explain how his office would pay for the costs of hiring Wester and his Charlotte-based law firm. Wester said he had been instructed to refer questions about the costs to McCrory's office.

In theory, lawmakers may not incur any extra cost to the state to defend themselves. Lawyers for the Attorney General's Office are salaried and do not bill an hourly rate. Lawmakers do have the option to hire outside counsel, but a spokeswoman for President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, said they have not decided whether to go that route.