State: Court can fund Leandro plan without General Assembly OK

North Carolina would not need to raise any additional money nor pass new legislation to fund a court-ordered education equity plan, attorneys for the state say.

The North Carolina constitution’s promise of an education for all children is “itself, an appropriation made by law,” they wrote.

The nine-page filing was submitted by Attorney General Josh Stein’s office late Monday. It doesn’t endorse, and it doesn’t take issue with, a proposal last week from plaintiffs in the 27-year-old education funding lawsuit. The plaintiffs asked Superior Court Judge David Lee to order state finance executives to move $1.7 billion in unappropriated funds to three state entities to spend on education – bypassing the legislature. That would fund the second and third years of the court-approved plan.

The case at hand is the so-called Leandro lawsuit, first filed in 1994 by families in five low-wealth counties and those counties’ school boards against the state, alleging the schools weren’t sufficiently funded. Two North Carolina Supreme Court rulings favored the plaintiffs. The second ruling in favor came in 2004, when the court ordered the state to remedy its shortcomings, while giving sufficient deference to the General Assembly to do so.

The General Assembly, then led by Democrats and now by Republicans, has never submitted a formal plan to comply with the rulings. Some changes have been made since 2004 to education policy and funding, though not to an extent courts have found sufficient in periodic progress hearings.

Republican legislative leaders have argued the courts can’t set the budget and aren’t sold that the plan would close achievement gaps among students and schools. Proponents of the plan have called those gaps “opportunity gaps,” stemming from disparate resources.

Both the plaintiffs and the state this spring submitted a plan to Lee, who oversees the case, and he approved it in June. It will cost at least $5.6 billion total over eight years, with some expenses, such as salary increases, remaining permanent.

The plan’s main goals are to ensure high-quality teachers in every classroom, high-quality principals in every school and more North Carolina children with access to pre-kindergarten. Within the plan are numerous suggestions for adding or changing laws and policies, such as removing the cap on funding to educate children with disabilities.

Current House and Senate leadership has said they don't plan to include the plan in their budget proposals for this year and next.

In the filing Monday, the state acknowledged findings with which it had not complied.

“In fashioning a remedy, the court should take note of two important features of the current situation,” state attorneys wrote. “First, an appropriate remedy does not require generating additional revenue.”

The State Treasury, Stein’s office wrote, contains more than the $1.7 billion required for this year and next year, under the plan.

Second, attorneys wrote, no new legislation would be needed to “fulfill the constitutional mandate.”

“That is because the people of North Carolina, through their Constitution, have already established that requirement” for an education for all children.

“The General Assembly’s ongoing failure to heed that constitutional command leaves it to this Court to give force to it,” state attorneys wrote.

The filing doesn’t say how Lee should proceed without lawmakers. In previous court hearings, Lee mentioned how judges in other states have forced lawmakers’ hands, by issuing fines for noncompliance, among other things.

In conclusion, the state does not suggest Lee do anything but acknowledges Lee’s intention to do something.

“The State further understands that the Courts and the Legislature are coordinate branches of the State government and neither is superior to the other,” Stein’s office wrote. “Likewise, if there exists a conflict between legislation and the Constitution, it is acknowledged that the Court,” citing a 1975 ruling, “’must determine the rights and liabilities or duties of the litigants before it in accordance with the Constitution, because the Constitution is the superior rule of law in that situation.’”

But GOP lawmakers said Stein and Lee are trying to overturn decades of legal precedent that gives the General Assembly sole control over state spending.

"Attorney General Stein's 'defense' is yet more evidence that this circus is all about enacting Gov. [Roy] Cooper's preferred spending plan over the objections of the legislature, the only branch legally authorized to make spending decisions," Sen. Deanna Ballard, R-Watauga, co-chair of the Senate Education committee, said in a statement.

"Any attempt to circumvent the legislature in this regard would amount to judicial misconduct and will be met with the strongest possible response," House Speaker Tim Moore said in a statement, adding that Stein treats the state constitution merely as "a suggestion on how to perform his duties."

Democrats respond

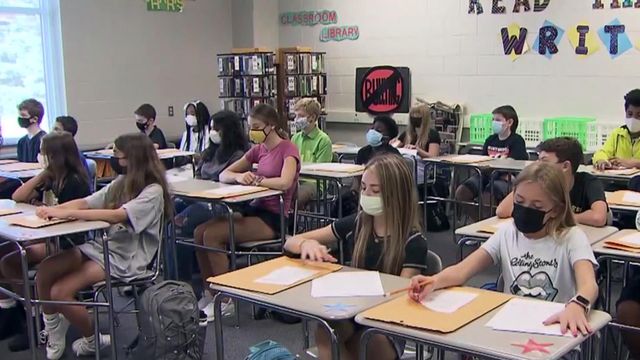

On Tuesday, Democratic lawmakers and Leandro plan advocates held a news conference to push for funding the Leandro plan and for a new report they say illustrates many schools’ dire need for the plan.

At the time of the news conference, officials had not seen the filing from Stein’s office. Afterward, Sen. Jay Chaudhuri, D-Wake, sent a statement to WRAL News.

“While I acknowledge and respect the defendant's arguments regarding the role of the legislature, it remains the duty of our independent judiciary to determine whether or not our executive or legislative branch runs afoul of the state constitution, including an affirmative right and remedy to sound basic education.”

During the news conference, Leandro plan advocates discussed their new project, “True Reports of Underfunded Education.”

The project collected first-person testimonials submitted on its website about how schools are underfunded and what lawmakers can do about it.

The most-reported issue – 122 reports – was staffing shortages affecting whether students get to class on time, altered curriculum and teachers skipping lunches and planning periods to cover other classrooms. Another 87 reports concerned long hours and feeling burned out. Other reports reference supply shortages, infrastructure issues, high class sizes and safety concerns.

A teacher in Currituck County reported she had to buy furniture for her new modular classroom and that she was also responsible for cleaning the bathroom in it, said Bryan Profitt, a high school history teacher and vice president of the North Carolina Association of Educators.

“That educator isn’t feeling thanked or supported,” Profitt said.

Cristo Salazar, a recent Yadkin County Schools graduate, said he fell behind in school when he was removed from classes to to learn English. He had to find a way to catch up on his own in high school, he said. He works now but still hopes to attend college.

Salazar said he still wishes things had been better and criticized legislative leadership for not helping more to provide students with a better education.

“They are prioritizing tax cuts over providing students with public schools that meet constitutional standards,” he said.

Infrastructure is the responsibility of counties, while education is the responsibility of the state. Many counties levy property taxes for education beyond infrastructure, to offer higher pay to teachers or hire more staff, among other things. Counties identified $12.8 billion in infrastructure needs over the next five years.