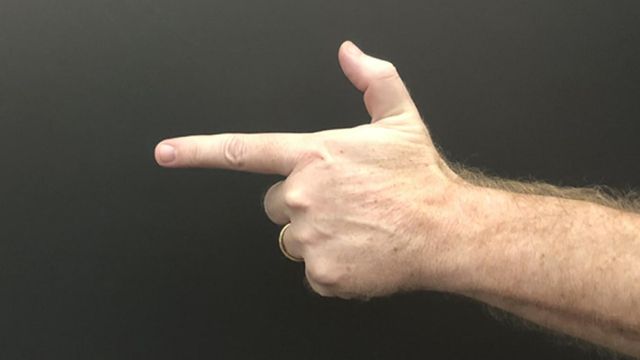

Kansas middle-schooler charged with felony after making gun shape with fingers

A Kansas middle school student was arrested after making the shape of a gun with her fingers and pointing it at others. That student now faces a felony charge, an official said.

Last month, Shawnee Mission School District officials were made aware of a potential threat by a student at Westridge Middle School through the district’s website, where students can report safety concerns, the Overland Park Police Department said in a statement.

An offense report from the department said that the incident occurred Sept. 18, and that the police responded the next day.

District officials and staff members at Westridge Middle School, which is in Overland Park, about 10 miles southwest of downtown Kansas City, were then made aware of the threat, according to the statement. The student, a 13-year-old girl whose name was not released, was questioned by school officials and a police officer assigned to the school.

During the questioning, the student “affirmed the actions” and was arrested, the statement said.

“The arrest was not something that we or anybody in our employment did,” David A. Smith, the school district’s chief communications officer, said Friday. “It was something that was done by the Overland Park Police Department.”

The girl faces a criminal threat charge, which is a felony, Kristi Bergeron, a spokeswoman for the Johnson County district attorney, said Friday.

The student was released after some “testing,” Bergeron said, adding that the student was scheduled to appear in juvenile court next week.

Bergeron declined to give additional information about the case but noted that “over 40% of all juvenile offenders receive some sort of diversion,” which keeps them from having a criminal record.

Smith, who declined to say whether the student was attending classes or faced expulsion, said the district does not use “zero tolerance” language in its policy about threats. “We look at cases individually,” he said. “We try to look at, Does this student have the actual motivation to meet a threat? Do they have the means and the opportunity to carry the threat out?”

Over the past year and a half, there were about a dozen instances in which students in the district made threatening gestures with their hands, he said.

“To my knowledge, none of the other students have been arrested,” Smith said.

However, there have been a variety of consequences handed down, the strongest being a three- to five-day suspension, he said, adding that a letter about the recent incident was not sent out to all parents. However, the Westridge principal did speak to the parents of students involved in the matter.

Juvenile incarceration is not uncommon: More than 800,000 minors were arrested in 2017, according to the United States Department of Justice.

Two 6-year-olds were arrested in separate incidents last month at a charter school in Orlando, Florida. One of the children had kicked a staff member, and both faced battery charges that were later dropped. In March, a 17-year-old was arrested in Charlottesville, Virginia, in connection with a threatening “ethnic cleansing” post online that forced the city’s public schools to close for two days.

In February, an 11-year-old student was arrested in Lakeland, Florida, after he disrupted the classroom and refused to participate in the Pledge of Allegiance. In 2015, a 14-year-old was detained and handcuffed after bringing a homemade clock to a high school in Irving, Texas, that was mistaken for a bomb. He was suspended from school for three days, but no charges were filed. (President Barack Obama later invited him to the White House for an astronomy event.)

According to Elizabeth S. Barnert, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, the rate of juvenile incarceration has decreased in recent years, but the United States still imprisons more minors than anywhere else in the world.

“I think the evidence is pretty clear that involvement in the juvenile justice system is harmful, traumatic and should be used as a last resort,” said Barnert, who studied the relationship between children who were incarcerated and their health outcomes into adulthood.

Her research found that children are often exhibiting normal developmental behavior when detained, and that children of color are arrested at a disproportionate rate. We tell them that they are criminals and they start to believe it, she said.

“On a societal level, I think we need to figure out how to best meet a child’s needs,” Barnert said. “The health system and the educational system need to step up.”