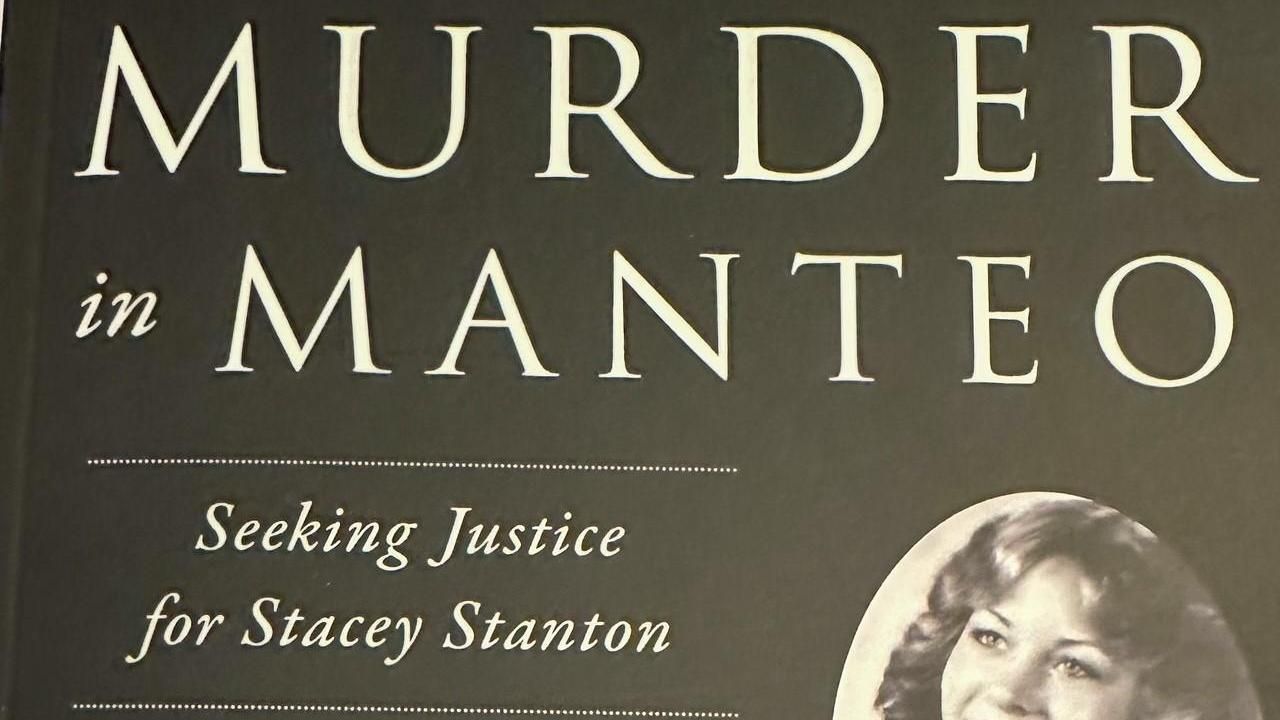

JOHN RAILEY: PART 2. Murder in Manteo - seeking justice for Stacey Stanton

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the second of two parts -- excerpt from John Railey's new book "Murder in Manteo; Seeking Justice for Stacey Stanton." Railey is a North Carolina journalist and author of two previous books the Outer Banks: "The Lost Colony Murder on the Outer Banks: Seeking Justice for Brenda Joyce Holland" and "Andy Griffith’s Manteo: His Real Mayberry." Read Part 1 here.

Chapter 10: A “Legendary Lawyer”

Manteo: Spring 1990 -- Clifton Eugene “Cliff” Spencer was charged in the spring of 1990 with Elizabeth Stacey Stanton’s slaying even though the case against him was flimsy at best. Despite North Carolina SBI testing, there was no evidence tying him to the crime scene, Stacey’s apartment, beyond his fingerprints. He’d admitted visiting with Stacey in the hours before she was killed, hence the fingerprints. Fingerprints of another main suspect, Norman Judson “Mike” Brandon Jr., Stacey’s ex-boyfriend, had also been found in the apartment.

Brandon, in an interview with law enforcement, had fingered Spencer as the potential killer. Brandon was white and Spencer was Black. In interviews with law enforcement, never videotaped or audiotaped, the notes often handwritten and transcribed weeks after the interviews, Spencer had denied killing Stacey.

Spencer’s family was apprehensive about having a court-appointed attorney out of Dare County represent him. There were few, if any, Black lawyers in the county on the local court-appointed list, much less any with experience in death penalty cases. Spencer’s family decided to raise funds to retain a lawyer for Spencer.

Through friends, they learned of Romallus Murphy of Greensboro. His record was impressive. He had completed his undergraduate studies at Howard University, started law school there and finished at the University of North Carolina School of Law where he was the only student of color when he graduated in 1956. He hung out his shingle in Wilson.

In 1959 Murphy brought a voting lawsuit against the City of Wilson. He fought the case all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. His supporters said the case, though unsuccessful, helped persuade Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Spencer family, impressed by Murphy’s experience, retained him in June 1990, agreeing to pay him $20,000 for Spencer’s defense (about $46,000 in 2023 dollars), money they started to raise in their community. Murphy visited with Spencer at Central Prison in Raleigh and had telephone chats with Spencer’s mother. But then, Murphy became harder to reach.

Chapter 11: “Mrs. Spencer, They Want to Kill Your Son”

Raleigh: December 1990 -- District Attorney H.P. Williams, prosecuting the case against Spencer, obviously sensed weakness in Murphy. In a phone chat on Dec. 4, 1990, Williams told Murphy that in exchange for Spencer’s guilty plea, the charge against him would be reduced to second-degree murder and he would be sentenced to life in prison. The death penalty would be off the table.

In a follow-up letter to Murphy dated Dec. 7, Williams wrote: “This offer remains open until the January 7, 1991, session of Criminal Superior Court in Dare County.”

Williams played high-stakes poker with Spencer’s future, giving Murphy one month to play or fold with the emotional holiday season unfolding.

December 1990 was a hard Christmas season for Spencer in Central Prison in Raleigh, where he was being held for “safekeeping.”

Murphy, despite the money Spencer’s parents had agreed to pay him, had done little on the case -- not once going to the crime scene, conferring with investigators or interviewing potential witnesses. Instead, Murphy spent much of his time on the phone with his client’s mom, telling her that the odds were against her son as a Black man charged with killing a white girl in a Southern town. “Mrs. Spencer, they want to kill your son,” he told Spencer’s mother more than once.

Murphy made a rare visit to see Spencer in Central Prison in December. He told his client about the statements Spencer had allegedly made to investigators, but shared little else about the discovery evidence supplied by prosecutors. “You are in trouble,” Murphy told Spencer. “There is nothing I can do for you.”

Spencer pushed back, saying that the statements weren’t true, noting that he had never signed them or written any of them. “It doesn’t make any difference,” Murphy told him. “That’s what the SBI is going to get up there and say that you did. There’s no way in the world you can win this case. I can get you a plea.” Spencer told his lawyer: “I’m not going to accept no f—— plea and I don’t want a plea.”

During the Christmas holidays, one of Spencer’s sisters, Karen, and his parents visited Spencer in Central Prison. Before the visit, Spencer’s family met with Murphy for breakfast at a Shoney’s restaurant in Raleigh. Between bites in the crowded room Murphy told them he had received the discovery.

“It doesn’t look very good for Cliff,” Murphy said. “He won’t stand a chance if he appears in court, the things that he said. The state really doesn’t have anything on him, but he talked too much, making incriminating statements.”

Murphy never mentioned that those statements might well be suppressed, given that Spencer had never signed them and his consent to them was questionable.

In the weeks ahead, Murphy accelerated his push on Spencer’s parents and Spencer for him to accept the plea offer from the state. Spencer continued to say he would not plead guilty to a crime he did not commit.

Capitol Broadcasting Company's Opinion Section seeks a broad range of comments and letters to the editor. Our Comments beside each opinion column offer the opportunity to engage in a dialogue about this article. In addition, we invite you to write a letter to the editor about this or any other opinion articles. Here are some tips on submissions >> SUBMIT A LETTER TO THE EDITOR