Jobless in the pandemic? You may be in a facial recognition database.

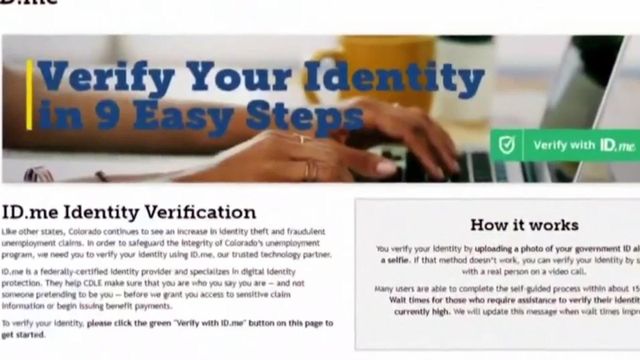

At the height of the pandemic, as unemployment surged across the country, tens of thousands of North Carolinians sent pictures of themselves to a private company—a new state requirement to confirm their identities—before they could get unemployment benefits.

It was an emergency measure meant to cut down on fraud as tens of thousands of jobless claims poured in daily to North Carolina’s overwhelmed Division of Employment Security.

The tradeoff—personal information for income in hard times—may have come at the expense of privacy. As many as 270,000 North Carolinians are now in a facial recognition database that the company planned to keep for up to seven-and-a-half years and, in some cases, share with law enforcement.

That’s in flux after pushback from privacy groups and members of Congress worried about the company’s rapid expansion. Virginia-based ID.me says it has contracts with 30 states, as well as some federal agencies, and that it provides “digital identity to 70 million Americans."

The company says it helped prevent billions in unemployment fraud nationwide as states grappled with massive jobless claim volumes that enabled fraudsters to hide within the system. The U.S. Department of Labor last year said some $83 billion may have gone out improperly, with “a significant portion” due to fraud.

But a federal plan to require facial recognition to access IRS records was a tipping point. After a backlash, the Internal Revenue Service said this month that it would drop those plans, and ID.me said it would let all ID.me users delete photos on file with the company beginning Tuesday by logging in to their account.

“ID.me is an identity verification company, not a biometrics company,” the company said in that announcement, using a catch-all word for images and other data that quantify physical features.

Deletions will take place within seven days of receiving a request, the company said in a statement Friday, but it wasn't clear how people will be informed that the option exists. "We are working through any communications with our state government agency partners," the company said.

A growing universe

Experts said ID.me’s government contracts represent one more privacy encroachment in a world rapidly implementing facial recognition technology, which uses computers to identify people by comparing their picture to a database of images.

The North Carolina Division of Motor Vehicles, for example, has an online portal that law enforcement can use to request facial recognition searches of the state’s drivers license database, no subpoena required. A DMV spokesman said he couldn’t say how often that happens because requests aren’t tracked.

A number of local governments have or are adding surveillance cameras with facial recognition capability. Two years ago the Raleigh Police Department said it would stop using a facial recognition service that had scraped billions of images from social media and the internet without people’s consent.

Earlier this month The Washington Post reported that this same service, Clearview AI, told investors it’s on track to have 100 billion photos in its database within a year, enough to ensure “almost everyone in the world will be identifiable.”

Even in that environment, ID.me’s case has some disconcerting conditions, according to privacy experts who advocate against facial recognition. People have to use the service to get certain government benefits, a private company controls the database and ID.me’s terms of service are difficult to suss out.

“You’re very much dependent on how ID.me interprets their own policy,” Jeramie Scott, senior attorney at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, said. “And given their wording, different aspects of the policy could be interpreted pretty broadly.”

Albert Fox Chan, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, as well as an attorney and a fellow at the Yale Information Society Project, also said some of the company’s policies are vague.

“It’s completely unclear to me how they’re using it with law enforcement,” Fox Chan said..

Most photographs online aren’t optimized for facial recognition, but ID.me can walk people through steps to get the type of picture it wants, he said. Given the large number of government customers the company added during the pandemic, Fox Chan said ID.me is “uniquely positioned to grow,” though the recent pushback may hamper that.

Before the IRS shifted gears, The Washington Post reported that the agency’s plan to use ID.me represented “one of the government’s biggest expansions yet of facial recognition software into people’s everyday lives.”

The company said in a statement that its data is encrypted and that “no third party organizations, including government agencies, have access.” ID.me said it only shares biometric data with the government in response to “a subpoena, or as part of an investigation into an identity theft or fraud case.” And then it shares data “only at the specific agency where the ID.me account was involved,” the company said.

ID.me declined to say how often it has shared photos or other personal information with law enforcement. The N.C. Division of Employment Services, which first contracted with ID.Me in December 2020, said it doesn’t know.

“We have no access to information collected by ID.me other than what’s required to process the individual's claim, including how ID.me has handled the information relative to its own privacy policy,” DES spokeswoman Kerry McComber said in an email.

‘What happens if …’

Kim Hall Worthington, who lives in Goldsboro, used ID.me to qualify for unemployment benefits in 2021 and complained, as many did at the time, that the verification process took about a month. She told WRAL News that she submitted a selfie, a picture of her driver’s license and a piece of mail to prove her identity.

On Friday, Worthington said no one had reached out to tell her of the company’s promise to delete database pictures on request.

The company’s biometric policy has actually said since at least June of 2021 that people can ask ID.me to delete their data, though it also says the company “may decline your revocation.” The policy also says terms can change at any time and that customers will be notified either on the policy page itself, by email or by a notice on the company’s home page.

Worthington said she didn’t know that the terms she agreed to with ID.me said the company would keep her picture for up to seven-and-a-half years. She worried about hacking and cases of mistaken identity.

“It really is a big concern,” she said. “What happens if the police show up at my door because somebody’s got an ID somewhere with my name on it?”

ID.me says that won’t happen. Privacy advocates say there are no guarantees.

“You really have to understand the full life cycle of how that data is going to be stored, sold and used,” Fox Cahn said. “What happens if they’re bought and sold? What happens if they go bankrupt? … There’s a lot of uncertainty about how this data could be used in the long run.”

DES said its contract with ID.me does not allow the company to transfer or assign its obligations to another company without DES approval, and that “any consolidation, acquisition, or merger … would have to be in writing and agreed to by ID.me, the [new company], and the state.”

‘A valuable tool’

North Carolina hired ID.me on a no-bid contract, saying in procurement documents that DES had “an urgent need” to beef up fraud detection without slowing down its own staff, which was overwhelmed processing claims and had “extremely limited” ability to verify people’s identity over the telephone or internet.

“It has proven to be a valuable tool,” McComber, DES’s spokeswoman, said in an email. “For example, identity verification requirements played an important role in preventing fraudulent payments when DES was flooded with 90,000 suspicious claims in late 2021.”

The division told state lawmakers in December that, out of $14 billion in unemployment payments since the start of the pandemic, “approximately $850 million has been identified as overpaid." But that's a broad category that includes, among other things, people who went back to work without reporting it and kept collecting benefits.

The division said Friday that about $100 million of these overpayments were due to fraud, and about $13 million of that was due to imposter fraud, in which a person’s stolen information was used to file a fraudulent claim.

So far DES says that about 270,000 claimants have started ID.me’s verification process, and that about 192,000 completed it. The others either were unsuccessful or didn’t finish the process, McComber said. The division has re-upped or amended ID.me’s contract three times over the last year, increasing it to cover as many as 300,000 verifications for $1 million.

Unemployment claims have dropped dramatically since the height of the pandemic, to between 3,000 and 3,500 claims a week, and what was initially a crisis response with ID.me has become part of regular procedure at the division.

In its statement earlier this month, announcing that people could delete their pictures from its database, ID.me also said it will give agencies that use its services the option to verify people’s identities without using automated facial recognition. Instead, users would verify through a video chat with an ID.me employee, a process already in use for some cases. It involves holding documents up to the camera.

The company’s statement indicated government agencies, not individual users, would have to choose this option, which may mean higher costs.

“Agencies can now offer users an upfront choice to verify with a human agent, including through video chat or in-person, if the agency has also procured our offline option,” the company said.

The state’s Division of Employment Security said that it “will review and assess options as they are made available to us by the vendor.”

Some members of Congress have asked the U.S. Department of Labor to help state unemployment offices move away entirely from ID.me and any other private contractors using facial recognition.

“Facial recognition should not be a prerequisite for accessing (unemployment insurance) or any other essential government services,” Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, D-Ore, and other committee members told the department a letter this month.

“It is concerning that so many state and federal government agencies have outsourced their core technology infrastructure to the private sector,” the senators wrote. “It is particularly concerning that one of the most prominent vendors in the space, ID.me, not only uses facial recognition and lacks transparency about its processes and results, but frequently has unacceptably long wait times for users to be screened by humans after being rejected by the company’s automated scanning system.”

Through a spokesperson, ID.me declined to respond to the letter Friday.