By a slim vote, NC education committee recommends overhaul in how teachers are paid and supported

A “blueprint” for how to reform North Carolina’s teacher licensure system — to include more evaluations and tie licenses directly to much higher salaries — is headed to the State Board of Education.

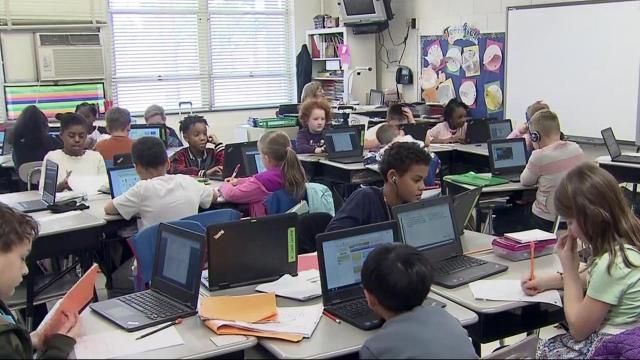

Licensure reform would mean major changes for the state’s more than 100,000 public school teachers that use the system, as well as their principals and their more than 1.5 million students statewide. It would increase educator evaluations and observations, as well as teacher support and pay in an attempt to keep more teachers in the classroom. Opponents have questioned how it would be implemented and funded.

The Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Committee voted 9-7 Thursday to move the “blueprint” for a new licensure system forward. The committee pivoted from plans to submit a more specific and robust recommendation for overhauling teacher licensure and instead landed on a one-page “blueprint.”

The “blueprint” is a list of 10 general actions to change teacher licensure, rather than an outline of steps, measurements or numbers that would be included in an actual licensure system.

Those who favored the blueprint argued the proposed licensure system could and would change even after the blueprint was sent over. Superintendent Catherine Truitt, who voted for it, noted the General Assembly will begin work for its long session in just weeks.

“I think the last thing we want is for the General Assembly to move on without us, and that is why time is of the essence,” Truitt said.

Several committee members said they still don’t agree on many more specific potential changes to the system. Some had more fundamental issues with the committee’s existing drafts of a new licensure system. Those drafts are not in the blueprint but are the basis for how the committee has approached revising the system.

“I am concerned about this becoming a model that relies too heavily on standardized tests as an outcome measure for evaluations,” said Scott Elliott, Watauga County Schools superintendent and a committee member.

Approval of the blueprint almost never happened during Thursday’s virtual committee meeting. The vote was tied 7-7, with four members not voting, until two of those members returned to vote in favor of it. One was Sam Houston, President and CEO of the North Carolina Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education Center. Houston had made the motion to approve the blueprint in the first place but was disconnected from the meeting and struggled to reconnect before he could vote, which he ultimately did via speakerphone on another attendee’s phone.

A tie vote would have meant the blueprint failed to pass, but Department of Public Instruction General Counsel Allison Schafer said Houston, in particular, could vote upon return because he had been involuntarily disconnected from the meeting.

State education leaders are mulling major changes to the licensure system following a 2017 directive from the North Carolina General Assmebly to do so.

The changes, as drafted, would shift the current licensure system from one based on experience and continuing education to one based on performance evaluations and continuing education. The current system has no ties to salary, but the draft system would tie a base salary amount to the license the teacher has and how many years they’ve had it, with pay rising as a teacher meets more requirements and teaches more years. For fully licensed teachers, base pay would be $56,000 — higher than the current maximum pay.

Facing an educator shortage, leaders want to raise interest in teaching as a profession and keep the teachers it has already. For years, the state has produced far fewer teachers than leave the teaching profession here each year. A new licensure system would affect teachers and school systems across North Carolina, while leaders note the challenges to recruitment and retention vary district-to-district.

North Carolina’s proposed licensure system would be unique, and just the third nationwide to require teachers to prove they are effective to obtain a full teaching license.

The State Board of Education meets again Nov. 30 and Dec. 1, with voting scheduled for Dec. 1. If the board approves the blueprint — and many members have said they favor it — the blueprint would be recommended to state lawmakers, who would then decide to take it up.

The ‘blueprint’

The one-page blueprint approved Thursday calls for, among other things, the state to include “advanced and lead teacher roles” to support other teachers at their schools. It also asks for the state to “create and adopt valid and reliable tools” to assess teachers’ impact on student learning.

It also acknowledges the funds required to pay for the pay raises, new teacher roles and other tools and support for making the licensure system work. The last goal listed asks to “secure funding to support the infrastructure” of the licensure system.

The measure passed Thursday is different than what officials had previously discussed voting on.

The committee declined to vote in October on a draft teacher licensure system.

Committee Chairman Van Dempsey returned this month with the “blueprint” and promising the committee would request to have a continued say going forward, even as other lawmakers potentially start working on a new system.

The blueprint allows the State Board of Education to move forward, rather than continuing to wait on the committee to agree on a new system, which many members said still needed significant work. Dempsey and others argued the committee could not wait to finalize every detail of a proposed system before recommending it and that it was not practical, if the State Board of Education or the General Assembly ended up rejecting or changing it.

The committee, by the state law that created it in 2017, is charged with making recommendations on teacher licensure, not the State Board of Education, which can only ask lawmakers change licensure statutes, Dempsey said. So the committee’s work wouldn’t end after approving the blueprint, he said, and it can keep working on the framework of the licensure model.

“I think this understanding of the statute ... actually gives us more time and more room to work toward the kinds of development of the framework itself and the components of the framework as we keep moving forward,” Dempsey said.

The committee must flesh out the details of a new licensure system once either the State Board of Education or General Assembly directs them to, before it can be implemented.

While the law states the committee is supposed to develop the licensure system, the committee has largely revised a model given to them from what state officials have argued was a non-public group called the Human Capital Roundtable, facilitated by the publicly funded Southern Regional Education Board using funds from the Gates Foundation. The roundtable was comprised Department of Public Instruction employees, State Board of Education Member Jill Camnitz and other education leaders in the state. The system mirrors one the Southern Regional Board of Education proposed for Mississippi before the group proposed a system for North Carolina. Mississippi has not adopted the system.

Potential impact on teachers

While an overhaul of North Carolina’s teacher licensure system may be years away from showing up in classrooms, the proposal has caught the attention of the state’s more than 100,000 public school teachers. Feedback received by the state and nonprofit group surveys this spring showed teachers had numerous questions and concerns about how the increased emphasis on evaluations would affect their ability to remain teachers, how much they’d be paid to teach, and the environment in which they work.

Many have wondered how many teachers would be forced out of the profession and whether competition or stress from high stakes evaluations would worsen the already taxing teaching profession.

A principal concern among teachers was that the committee’s draft licensure model didn’t spell out what all of the evaluation measures would be.

On Thursday, Tom Tomberlin, the state Department of Public Instruction's senior director of educator preparation, licensure, said very few teachers are currently not meeting expectations.

The licensure overhaul requires teachers to provide proof they are effective to obtain or maintain a full professional teaching licensure. In the model, but not the blueprint, the committee has defined that as proving effectiveness in three out of the past five years.

The way the state currently evaluates teachers in the NC Educator Effectiveness System — collection of measures that, individually, could be part of the model — just 43 teachers fall into the “needs improvement” category, Tomberlin said.

“We would have 43 teachers, which doesn’t even register as a percent,” Tomberlin said.

For the 40% of teachers who are subject to the Education Value-Added Assessment System — meaning, their students take the state’s standardized tests — just about 7% would fall into the “needs improvement” category. Those same teachers could elect to use another effectiveness measure, if they suspected they would fare better.

Those other effectiveness measures, primarily serving the 60% of teachers who don’t teach courses in which students take the state’s standardized tests, haven’t been selected yet.