Fact check: Trump says patients in 'bad' hydroxychloroquine study were 'almost dead'

The Food and Drug Administration cautions that hydroxychloroquine can hurt people. It increases the risk of an irregular heartbeat, which can lead to cardiac arrest. But President Trump recently dismissed dismiss research that cast doubt on whether the drug does any good against COVID-19.

Posted — UpdatedCount President Donald Trump as hydroxychloroquine’s No. 1 fan.

At a press conference, Trump told reporters he’s putting his health where his mouth is.

"Couple of weeks ago I started taking it," he said May 18. "Because I think it’s good. I’ve heard a lot of good stories. And if it’s not good, I’ll tell you right. I’m not going to get hurt by it."

To be clear, the Food and Drug Administration cautions that hydroxychloroquine can hurt people. It increases the risk of an irregular heartbeat, which can lead to cardiac arrest.

Trump didn’t mention that. He did, however, dismiss the research that cast doubt on whether the drug does any good against COVID-19.

"If you look at the one survey, the only bad survey, they were giving it to people that were in very bad shape," Trump said at a May 19 press event. "They were very old. Almost dead. It was a Trump enemy statement."

Later that day, Trump clarified that he was talking about a study of Veterans Administration patients.

Trump spoke as if there were only one negative study. There have been three: the one on VA patients and two larger ones. They all reached the same conclusion that outcomes with hydroxychloroquine were the same as without it.

The studies

The earliest work on hydroxychloroquine was small studies, sometimes with as few as 30 patients, and for each study that showed promise, another study found no benefit. The mixed results spurred more research.

They found that hydroxychloroquine, with or without the other drug, had no effect on whether someone had to be put on a ventilator. Worse, hydroxychloroquine increased the chances of dying.

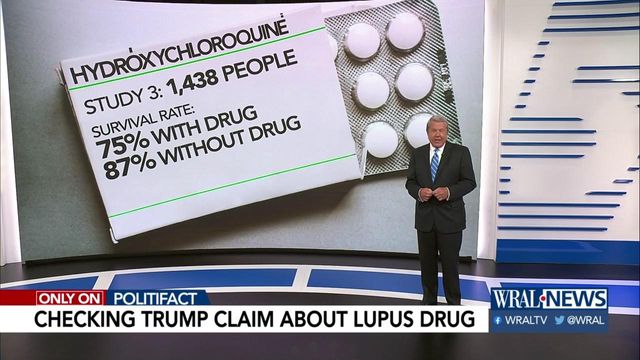

The authors cautioned that all of the patients involved in the study, regardless of outcome, were men over 65. And they also factored in a range of underlying conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure and other health risks. Those issues were found in roughly equal numbers across all groups of patients. Ultimately, about 75% of the patients getting hydroxychloroquine lived. The survival rate was close to 90% for those who didn’t get it.

Trump ignores larger, newer studies

In early May, two studies emerged based on patients treated in the nation’s biggest COVID-19 hotspot, New York City. Both investigations were much larger than the study of VA patients.

"There was no association between administration of the drug and a lower chance of dying or winding up on a respirator," said co-author Neil Schluger, the head of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Now, it’s fair to say that the patients who got the drug were, as a group, a bit worse off than those who didn’t. In particular, their blood oxygen levels were lower when they were first admitted. Schluger said that didn’t matter.

"The difference in oxygen levels between the two groups we compared were fairly small and not clinically important," Schluger said.

These patients were not close to death, Schluger said.

"Overall, about 83% of the patients in our cohort survived, and that survival had no association with hydroxychloroquine administration," he said.

Like the other study, this one found that patients who got the drug were in worse health at admission than those who didn’t. They might have lower oxygen levels, or some other condition such as diabetes or obesity.

But by examining patients’ full medical records, both teams were able to use stronger analytic tools to filter out the impact of differences in underlying health. Once that was done, they could make apples-to-apples comparisons of the effect of hydroxychloroquine on people who got the drug and those who didn’t.

The authors of all studies acknowledged that working with patient records after the fact isn’t the final answer, and they called for more research.

We reached out to the White House and did not hear back.

PolitiFact ruling

Trump spoke about "the one survey," a study of VA patients and hydroxychloroquine, and said it was "bad" because "they were giving it to people that were in very bad shape. They were very old. Almost dead."

There have been three studies, not just one. None of them found that the drug reduced the death toll.

As a group, the patients getting the drug were not on the verge of death. Across three studies, about 75% to 80% of the patients receiving the drug survived.

To say they were in very bad shape is also off the mark. Health issues were found in members of both the treatment and non-treatment groups. That allowed researchers to tease out the impact, and make informed comparisons that took these health differences into account.

We rate this claim False.

Related Topics

Copyright 2024 Politifact. All rights reserved.