A Houston High School has a new dress code - for parents

A school dress code has once again set off a heated discussion about race, class and cultural norms. Only this time, the dress code is aimed at parents, not students.

Posted — UpdatedA school dress code has once again set off a heated discussion about race, class and cultural norms. Only this time, the dress code is aimed at parents, not students.

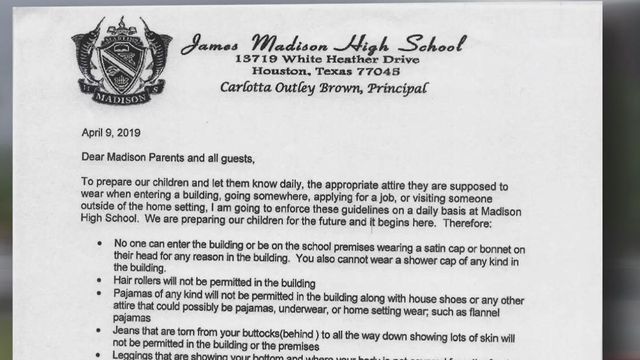

James Madison High School, a public school of about 1,600 students in Houston, notified families this month of a sweeping policy that banned revealing and sagging clothing for all people visiting the school, as well as pajamas, hair rollers, and satin caps and bonnets, which are often worn by black women to protect their hair.

“You are your child’s first teacher,” the principal, Carlotta Outley Brown, wrote in a letter dated April 9 that asked adults to set an example by wearing appropriate attire on campus and helping support the school’s high standards.

“We are preparing your child for a prosperous future,” she added. “We want them to know what is appropriate and what is not appropriate for any setting they may be in.”

The letter came a day after a local television station reported that a mother said she had been turned away from enrolling her daughter at the school because the mother was wearing a short dress and a head scarf. The policy has since ricocheted across Houston and beyond, with many calling it another example of how policies on personal appearance can enforce racist and classist power structures.

Controversies over dress codes frequently spring up in education, where people of color, especially young women, often bear the brunt of rules governing attire. Black girls have been asked not to wear braided hair extensions and African head wraps to school and, last year, New Jersey state officials opened a civil rights investigation after a black high school wrestler with dreadlocks was forced to cut his hair to compete in a match.

The policy for parents in Houston, at a school that is 58% Hispanic and 40% black, and where three-quarters of students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, drew strong reactions online and in the community. Critics said the focus on hair hurt black women, while the rule against pajamas and housewear seemed to target lower-income families.

Roni Dean-Burren, a former teacher who studies literacy and school discipline and lives in Houston, spoke out on Twitter, saying the rules policed black women’s hair and bodies in ways that were not equally applied to white women “wearing leggings and wet yoga hair to their kids’ school.”

In a phone interview, she said the school’s focus should be on student success and family engagement, not on how parents look. “It’s so far down the list of things to be concerned about,” she said.

Ashton P. Woods, a community activist who is running for Houston City Council, denounced the policy as elitist and a form of respectability politics. “Most of the parents likely cannot afford to comply with this dress code,” he tweeted.

The principal, Outley Brown, who is black, did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday.

The Houston Independent School District, the largest school district in Texas, declined to comment.

Dorinda Carter Andrews, the associate dean for equity and inclusion for the college of education at Michigan State University, said that educators have the right to be clear about what kind of attire is appropriate in schools, including which clothing is too revealing. But she said the policy in question inappropriately included rules against hair coverings and housewear.

“There is a fine line here around a socially constructed high standard that is based on norms that aren’t inclusive,” she said, adding that black women’s bodies and hair in particular have been policed historically.

“That has been so problematic historically and in contemporary times for black women, because our hair is like a representation of self,” she said.

The idea of imposing restrictions on parents’ dress has taken root in fits and starts in recent years, primarily in an effort to discourage adults from wearing inappropriate or revealing clothing on school campuses. A bill in Tennessee that would have required school districts to establish codes of conduct for everyone on school property stalled this year. In 2014, a school board in Florida considered, but ultimately rejected, imposing a dress code for parents.

The policy in Houston is not without its supporters. Online, some people spoke up in agreement, lamenting that a policy asking parents to dress appropriately had to be written out in the first place.

Roshelle Ruffin, whose daughter is a sophomore at James Madison High School, said that she sees parents coming to school looking as if they are “rolling out of the bed,” which she said had a trickle-down effect on the students.

“Presentation is everything. The way you carry yourself shows a lot about yourself,” said Ruffin, who is black and said she agreed with the decision to prohibit bonnets. “If you can get dressed up to do other things, you can definitely get yourself prepared to go to your child’s school.”

But as schools grapple with the issue, they engage in a delicate dance between encouraging adults to serve as role models for students and potentially ostracizing the very parents they want to engage.

“If we really want to lead and bring people up to a higher standard and elevate people, then we bring them in, rather than push them out,” said Zeph Capo, president of the Houston Federation of Teachers. Carter Andrews, who is also an associate professor of race, culture and equity at Michigan State, encouraged schools to handle problems with attire by having individual conversations with parents, rather than a blanket policy.

“They may themselves have had negative experiences with schooling so this practice is really another way to further marginalize them, instead of cultivate a relationship,” she said.

Joselyn Lewis, the mother in Houston who said she was turned away this month because of her attire, told Channel 2 News that she had worn a T-shirt dress and head wrap to enroll her 15-year-old daughter, who was being bullied at another school.

At first she thought the school had mistook her for a student, she said, before learning that a standard of attire indeed applied to parents.

“I don’t have to get all dolled up to enroll her to school,” she said. “My child’s education — anyone’s child’s education — should be more important than what someone has on.”

Copyright 2024 New York Times News Service. All rights reserved.